Home » Practice Papers » Social Capital Impact Assessment (SCIA) » Social Capital Impact Assessment (SCIA)

Social Capital Impact Assessment (SCIA)

Foreword

The Institute for Social Capital published this practice paper in response to growing recognition that many of the most significant risks and opportunities facing organisations, projects, and public institutions are social in nature, yet remain poorly assessed. Decisions that appear technically sound and procedurally compliant often encounter difficulty over time, not because of flaws in design or execution, but because the social conditions required for cooperation, legitimacy, and collective action have been weakened or overlooked.

Across policy, infrastructure, organisational change, and community investment, social considerations are increasingly acknowledged but still commonly treated as immediate responses to manage rather than as sources of future capacity to be stewarded. As a result, impact assessment often emphasises short-term outcomes and observable behaviour, while the longer-term social conditions that shape ongoing viability remain implicit.

This paper introduces Social Capital Impact Assessment (SCIA) as a way of addressing this gap. It does not propose social capital as an additional impact category, nor does it seek to replace existing assessment or engagement practices. Instead, it presents social capital as a lens for understanding how decisions shape the social capacity on which future performance, legitimacy, and adaptability depend.

The Institute for Social Capital is committed to advancing understanding of social capital in ways that are both conceptually robust and practically useful, and this paper reflects that commitment. Drawing on social capital research, governance practice, and applied experience, it articulates a framework that helps decision-makers anticipate long-term social consequences and steward the conditions that support collective action.

The paper is written for policy-makers, project leaders, impact assessment practitioners, and organisational decision-makers working in complex social contexts. Its purpose is not theoretical debate, but improved decision quality. By clarifying how social capital functions as a form of future capacity and how it can be assessed prospectively, the paper aims to support more durable, legitimate, and resilient outcomes.

As with all Institute for Social Capital practice papers, this publication is intended to contribute to ongoing discussion and learning. The Institute welcomes engagement, critique, and further application of the ideas presented here as part of a broader effort to improve how social capital is understood and stewarded in practice.

Executive summary

Social capital is a foundational condition of effectiveness wherever people work together. Productivity, efficiency, innovation, problem-solving, legitimacy, and adaptability all depend on the social capacity that enables individuals and organisations to coordinate, share information, accept authority, manage disagreement, and act collectively under uncertainty. Financial, physical, and human capital rely on these social conditions to be mobilised into lasting value. For this reason, social capital is already implicit in many impact assessment judgements, even when it is not named or examined directly.

This paper introduces Social Capital Impact Assessment (SCIA) as an opportunity to strengthen and extend existing impact assessment practice. SCIA does not propose a new class of impacts or replace established social impact assessment or engagement processes. Instead, it offers social capital as an impact assessment lens—a way of bringing greater clarity and structure to social considerations that practitioners already recognise as important, such as legitimacy, cooperation, institutional credibility, and willingness to act.

Used in this way, the social capital lens helps explain long-term trajectories that conventional assessments often observe but struggle to account for in advance. It shifts attention from immediate responses and surface indicators, such as participation or expressed attitudes, to the underlying social capacity that shapes whether cooperation, innovation, and collective problem-solving remain feasible over time. This perspective complements existing IA approaches by enabling more explicit consideration of durability, cumulative effects, and system robustness in the social domain.

To support this role, the paper adopts a capital-theoretic and system-level understanding of social capital. Social capital is treated as a durable form of social capacity that conditions future action, shaped through experience, governance arrangements, and social and digital infrastructure, and expressed under particular situational conditions. This framing does not replace familiar social concepts, but organises them around future capacity. Decisions inevitably draw upon and influence social capital, sometimes reinforcing future capacity and sometimes weakening it, often without that effect being made explicit.

The paper then sets out how this lens can be applied in practice through a structured SCIA process aligned with established impact assessment sensibilities. By distinguishing analytically between social capital as a stock of durable capacity, the environments that sustain it, and the contexts in which it is activated, SCIA supports earlier identification of social risks and opportunities and more deliberate consideration of how design and governance choices shape long-term capacity.

By making social capital more visible within impact assessment, SCIA enhances existing practice. It provides decision-makers with a clearer basis for anticipating social risk, recognising opportunity, justifying investment in social conditions, and managing trade-offs between short-term performance and long-term robustness. Treated in this way, social capital becomes a valuable extension of current methods, helping impact assessment more fully account for the conditions on which durable performance, legitimacy, resilience, and shared wellbeing depend.

Table of Contents

- Social Capital Impact Assessment: The opportunity

- Social capital and the role of impact assessment

- What SCIA is designed to do

- The social capital system: what the impact lens reveals

- The core questions the social capital lens enables

- Applying the social capital lens in practice: the SCIA process

- Methods aligned to the social capital system.

- What SCIA enables in practice

- How SCIA complements existing frameworks

- From social outcomes to stewardship of social capacity

- References

- Further information

List of Figures

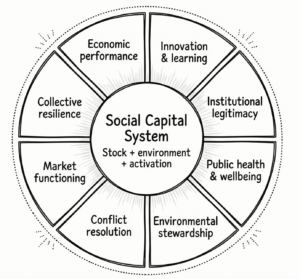

Figure 1. Domains of Service Generation (Non-Exhaustive)

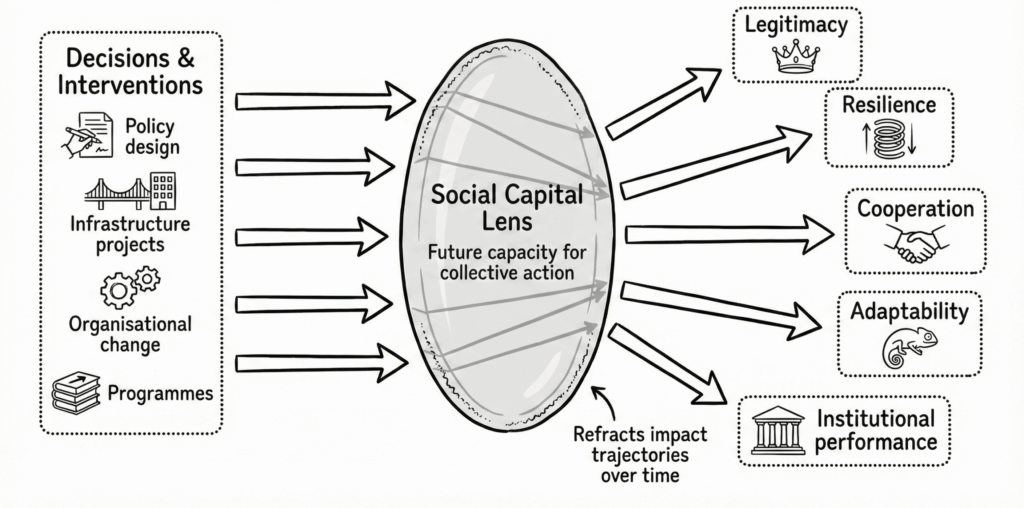

Figure 2. Social Capital as an Impact Lens

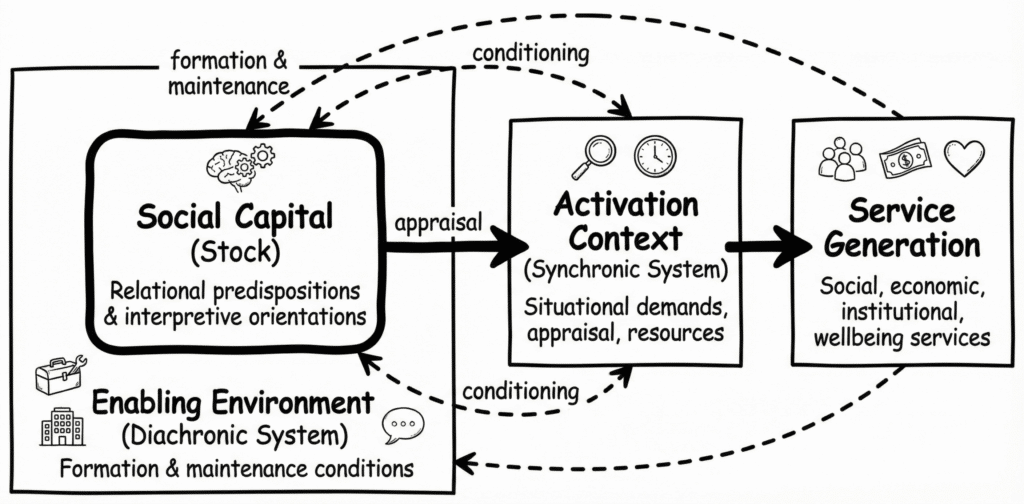

Figure 3. The Social Capital System

Figure 4. The enabling environment for social capital formation and maintenance

Figure 5. Activation context and expression of social capital

Figure 6. The Social Capital Impact Assessment Process

Figure 7. Social Capacity Risk & Opportunity Matrix

List of Tables

Table 1. Core SCIA Questions: SCIA shifts the focus from immediate social response to future feasibility

Table 2. Summary of analytical purpose and possible methods

Table 3. Comparison of SCIA, Social Impact Assessment, and Stakeholder Engagemen

1. Social Capital Impact Assessment: The opportunity

Social Capital Impact Assessment (SCIA) presents an opportunity to strengthen practice by reframing social concerns through a capital lens. Rather than introducing new social issues or redefining what matters, SCIA changes how familiar social considerations are understood and treated in assessment. When framed as capital, social concerns are understood as contributors to future capacity, with durable causal significance for long-term outcomes across multiple domains (refer to Figure 1).

Impact assessment concerns how decisions shape future conditions. Across domains, practitioners look beyond immediate effects to consider how interventions influence long-term productivity, resilience, and wellbeing. Social considerations are already central to this work. Issues such as legitimacy, trust, cooperation, inclusion, and procedural fairness are routinely examined because they affect whether decisions remain workable, accepted, and adaptive over time.

While social issues are recognised as important, their role in shaping future capacity is frequently left implicit, making it difficult to compare social risks and opportunities with other long-term considerations or to trace how they accumulate over time.

As a form of capital, social capital can be understood as something that is accumulated, drawn upon, and altered over time through decisions and experience.

Social capital can be invested in, maintained, or inadvertently depleted, with consequences that shape a range of substantive outcomes long after individual interventions are complete. Recognising social concerns in these terms allows impact assessment to engage explicitly with how present choices condition future capacity, and to treat the stewardship of social capital as a material consideration in long-term decision-making rather than an incidental or residual social effect.

Many social impacts assessed in practice, such as belonging, recognition, institutional credibility, and willingness to cooperate, are widely acknowledged as important.

What is often difficult is to explain their relevance in ways that are comparable with other assessment dimensions. Without a capital framing, these impacts can appear diffuse or secondary, even when they are central to long-term success.

What the capital framing adds is a way of making their value explicit and decision-relevant. Treated as capital, these social conditions are no longer understood only as desirable states or issues to manage in the present, but as part of the capacity on which future productivity, resilience, and wellbeing depend.

This reframing connects social considerations directly to outcomes that impact assessment already treats as material, including delivery risk, institutional performance, adaptability, and long-term value creation.

This opportunity exists because capital is defined by its causal role. Capital logic focuses attention on how accumulated conditions shape future possibilities—what becomes feasible, reliable, or fragile over time as a result of present decisions.

Applied in this way, the capital lens aligns social analysis with the core purpose of impact assessment (refer to Figure 2 on page 3). It supports judgment about future feasibility and risk under uncertainty, rather than post-hoc explanation of outcomes.

Applied to social concerns, this logic shifts assessment away from surface responses and toward durability. Cooperation, participation, or compliance may appear in some situations and not others; what matters for long-term impact is how decisions affect the underlying social capacity that supports such responses.

Framing social concerns as capital, therefore, changes the kinds of questions impact assessment can ask.

Instead of focusing only on whether social responses are positive or negative at a given moment, SCIA enables assessment of how decisions shape future social capacity itself. It becomes possible to identify when short-term success is achieved by drawing down that capacity, when apparent stability masks growing fragility, and when early design choices quietly set long-term trajectories. In doing so, SCIA helps explain why technically similar interventions can diverge significantly over time.

SCIA thus offers impact assessment a clear opportunity: to apply capital logic to social considerations that are already known to matter, making their long-term significance explicit, comparable, and governable.

In this sense, SCIA does not expand the scope of impact assessment, but deepens it. It strengthens existing practice by making a critical source of future capacity visible at the point where decisions are made.

This opportunity is significant because the ideas associated with the concept of social capital are already embedded in the assumptions that underpin most decisions, even when they are not made explicit. Policies, projects, and organisational changes routinely presume some level of cooperation, institutional credibility, willingness to share information, and capacity for coordination.

These assumptions influence expectations about delivery, risk, and long-term performance, yet they are rarely examined directly. SCIA provides a way to surface these implicit dependencies and to consider how decisions may strengthen, strain, or reshape the social capacity on which outcomes depend, without introducing new objectives or expanding assessment scope.

Like other forms of capital, its condition is shaped incrementally. Repeated interactions, institutional practices, and governance arrangements reinforce or weaken social capacity in ways that may not be immediately visible but nevertheless condition future action. This makes social capital particularly relevant to impact assessment, which is concerned with cumulative effects and long-term trajectories rather than isolated events.

The sections that follow build on this foundation by explaining why impact assessment is the appropriate governance setting for this form of analysis, and what SCIA is designed to do in practice.

2. Social capital and the role of impact assessment

If social concerns are understood as contributors to future capacity, the practical question becomes how those effects should be governed within decision-making processes. Impact assessment is designed for precisely this purpose. Its function is not to ensure particular outcomes, but to support responsible judgment under uncertainty by making long-term consequences visible at the point where choices are made.

Across established practice, impact assessment is used to examine how decisions affect future capacity and risk in domains where consequences accumulate over time. It provides structured ways to consider durability, cumulative effects, thresholds, and resilience, even when causal pathways are complex, and outcomes unfold gradually.

When social concerns are framed as capital, they exhibit these same characteristics. They develop over time, are shaped by repeated experience and institutional conditions, and influence future feasibility in ways that may only become apparent well after implementation.

Impact assessment is particularly well suited to addressing these effects because changes to future social capacity are rarely obvious at the moment decisions are taken. Choices made to optimise short-term performance, manage immediate risk, or accelerate delivery can alter social conditions in subtle ways whose consequences emerge only later.

Box 1. Similar projects, different trajectories

Two infrastructure projects are delivered with nearly identical technical design, budgets, and timelines. Both are completed on schedule and meet their immediate performance targets.

Project A proceeds through tightly controlled consultation, emphasising efficiency and risk containment. Early engagement metrics are strong, approvals are secured, and construction proceeds smoothly. Over time, however, local cooperation declines. Minor issues escalate into disputes, compliance costs increase, and future upgrades face growing resistance. What initially appeared successful becomes progressively fragile.

Project B takes longer to design and requires greater upfront coordination. Decision processes are more transparent, roles are clearer, and local actors experience meaningful influence over sequencing and implementation. Early delivery is slower, but cooperation strengthens over time. Subsequent changes are easier to implement, conflicts are resolved informally, and the project becomes a platform for further collective initiatives.

What the social capital lens reveals:

Both projects achieved short-term outcomes, but they shaped future social capacity differently. Project A drew down social capital to secure early delivery, weakening the system’s ability to support future action. Project B strengthened the conditions for cooperation, enabling long-term value beyond the original scope. A SCIA would have made these divergent trajectories visible before they fully emerged.

Without explicit assessment, these longer-term effects are easily overlooked or misattributed once difficulties arise. Impact assessment provides a forum in which such implications can be considered earlier, when they are more likely to be understood and acted upon.

Impact assessment also plays an important role in making investment in social capacity visible and defensible. Many of the conditions that sustain future social capacity, such as procedural integrity, institutional consistency, credible communication, and inclusive infrastructure, do not produce many immediate or easily measured outcomes.

When these conditions are considered only in terms of present response, they can appear discretionary or peripheral. Assessed in terms of their contribution to future capacity, their relevance to long-term impact becomes clearer and more comparable with other assessment considerations.

Positioning social concerns within impact assessment in this way strengthens governance coherence. Decisions about design, sequencing, approval conditions, and institutional arrangements routinely influence future social capacity, yet are often evaluated primarily for their immediate technical or procedural implications.

Impact assessment provides a setting in which these choices can be examined systematically for their longer-term social consequences, supporting more deliberate consideration of trade-offs between short-term efficiency and long-term robustness.

In this sense, SCIA extends the core logic of impact assessment to a form of capacity that is already relied upon but rarely governed explicitly.

The next section clarifies what SCIA is designed to do in practice, setting out its purpose, scope, and limits before the assessment framework and process are introduced.

3. What SCIA is designed to do

SCIA is designed to assess how decisions shape the social conditions that underpin long-term productivity, resilience, and wellbeing.

Its purpose is not to evaluate social outcomes in isolation, nor to substitute for existing social assessment or engagement practices, but to examine how policies, projects, organisational arrangements, and governance choices affect future social capacity.

This focus reflects a shift in analytical emphasis rather than a change in substantive concern. The social issues examined through SCIA, such as legitimacy, cooperation, institutional credibility, and willingness to act, are already familiar to impact assessment practice. What SCIA adds is a way of examining how these conditions are shaped over time by decisions, and how they influence what remains feasible or fragile in the future.

At its core, SCIA focuses on future capacity. It asks how decisions alter, over time, the durability and reliability of the social conditions on which collective functioning depends.

This orientation allows assessment to register impacts that may not be immediately visible, and to consider their implications before they manifest as operational, institutional, or community-level difficulties.

SCIA is designed to support prospective judgment under uncertainty. It does not attempt to predict specific social behaviours or guarantee particular outcomes. Instead, it examines how decisions influence the conditions under which social capacity is more or less likely to be available when needed. This approach aligns with established impact assessment practice, which routinely evaluates future risk and resilience without claiming predictive certainty.

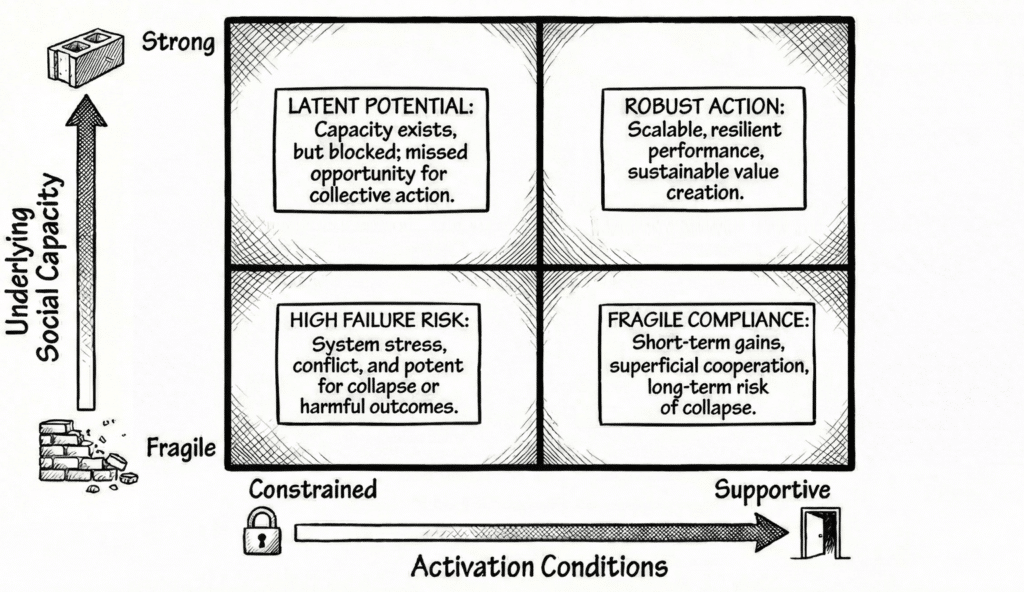

A central design feature of SCIA is analytical separation. The social capacity itself, the conditions that shape it over time, and the situations in which it is expressed are treated as distinct but interacting elements. This separation allows assessment to distinguish between weak capacity and constrained expression, between short-term compliance and durable legitimacy, and between apparent stability and underlying fragility.

Maintaining these distinctions improves diagnostic clarity and supports more targeted and proportionate responses.

SCIA is also explicitly oriented toward decision points where long-term trajectories are shaped. Choices about scoping, sequencing, governance arrangements, approval conditions, institutional design, and implementation all influence future social capacity, often in cumulative ways. SCIA brings attention to these influences at stages where they can still be adjusted, rather than after consequences have become entrenched and difficult to reverse.

Equally important are the limits of what SCIA is designed to do. SCIA does not treat social capacity as something that can be simply and explicitly engineered, optimised, or controlled. Social capital is actor-carried and interpretive; it is shaped through experience, observation, and meaning-making rather than command. The role of SCIA is therefore not to prescribe social behaviour, but to clarify the responsibilities associated with creating, maintaining, or degrading the conditions under which others may act.

In practical terms, SCIA supports a shift from implicit reliance on social capacity to explicit stewardship of the conditions that sustain it. It enables clearer justification for investments in social conditions, more informed trade-offs between short-term gains and long-term robustness, and earlier identification of social risks and opportunities.

Taken together, these design features position SCIA as a governance capability rather than a standalone assessment exercise.

It strengthens decision-making by making future social capacity visible at the point where choices are made, and by supporting more deliberate, proportionate, and forward-looking stewardship of the social conditions on which long-term outcomes depend.

The sections that follow describe how SCIA does this in practice, beginning with the social capital system that becomes visible when social concerns are treated as capital.

4. The social capital system: what the impact lens reveals

Using social capital as an impact assessment lens requires attention not only to outcomes but also to the system through which future social capacity is formed, sustained, and expressed. This system perspective is not introduced for theoretical completeness. It is what enables social capital to be assessed prospectively and meaningfully compared across decisions and contexts.

Viewing social capital as a system allows impact assessment to move beyond isolated social effects and toward an understanding of how decisions alter trajectories. Individual design choices, governance arrangements, or implementation practices may appear socially benign in isolation, yet interact over time to strengthen or weaken the conditions for cooperation, legitimacy, and coordination.

Without a system perspective, these cumulative and interactional effects are easily overlooked, making it difficult to explain why similar interventions produce different long-term outcomes.

For the purposes of impact assessment, social capital is treated as a durable form of social capacity.

It shapes how people orient toward others, institutions, and collective action over time, influencing whether cooperation, compliance, or coordination appear legitimate, worthwhile, or risky.

This capacity is carried by actors, shaped through experience and observation, and drawn upon when situations call for social action. Its durability matters because it allows past decisions and experiences to condition future possibilities long after specific interactions have passed.

This durability gives social capital particular significance for prospective assessment. Decisions taken today may leave immediate social responses unchanged while nevertheless altering the stock of social capacity that future decisions will depend upon.

A system view makes it possible to recognise these delayed and indirect effects, allowing impact assessment to engage with long-term feasibility rather than relying solely on short-term indicators.

Crucially, this capacity is latent. Social capital exists whether or not it is visibly expressed. Strong social capacity may remain unexpressed when conditions make action unsafe or ineffective, while visible cooperation may occur even where underlying capacity is thin, because circumstances temporarily compel compliance.

Treating social capital as latent capacity prevents assessment from relying on surface behaviour alone and reduces the risk of misdiagnosing both strength and fragility.

Recognising latency also helps explain why social dynamics can change rapidly once conditions shift. Apparent stability may persist until activation conditions change, at which point underlying weaknesses or strengths become visible.

A system perspective allows impact assessment to account for this possibility by focusing not only on what is currently observed, but on the conditions that shape how social capacity will be expressed in future contexts.

Taken together, these features explain why social capital must be understood systemically to function as an impact assessment lens.

The system perspective provides the analytical structure needed to assess how decisions shape future social capacity, to compare impacts across contexts and interventions, and to support judgements about long-term robustness rather than immediate response.

It is this perspective that allows social capital to be treated as a meaningful object of prospective assessment rather than as a descriptive label applied after outcomes are known.

To assess social capital in a way that informs decisions, SCIA distinguishes between three interacting components of the social capital system (refer to Figure 3):

- social capital as a stock of durable capacity.

- the enabling environment that shapes how that capacity is formed and maintained over time.

- the activation contexts in which it is expressed, or constrained, in practice.

These distinctions are analytical tools. They exist to clarify where impacts occur, how they accumulate, and what kinds of interventions are likely to be effective.

4.1 Social capital as a stock of durable capacity

At the centre of the system is social capital, understood as a stock of relational capacity. This refers to the accumulated orientations, expectations, and interpretive frames through which actors understand others, institutions, and collective situations. These orientations shape whether collective action appears plausible, whether authority is regarded as legitimate, and whether cooperation under uncertainty seems worthwhile.

As a stock, social capital is not tied to any single interaction or decision. It is formed through repeated experience and carried forward across situations, shaping how future contexts are interpreted before action occurs. Actors bring durable expectations about institutions and others into new settings, influencing what options appear available and sensible.

For impact assessment, the critical feature of this stock is its persistence. Because it endures beyond particular events, social capital allows past decisions to condition future action even when current behaviour remains unchanged. An intervention may leave immediate responses intact while still strengthening or weakening the relational capacity on which future initiatives depend.

4.2 The enabling environment: conditions that shape capacity over time

Social capital is formed, stabilised, and renewed within an enabling environment that operates over time. For assessment purposes, the enabling environment refers to the institutional, infrastructural, and experiential conditions that shape how social capacity develops and is sustained.

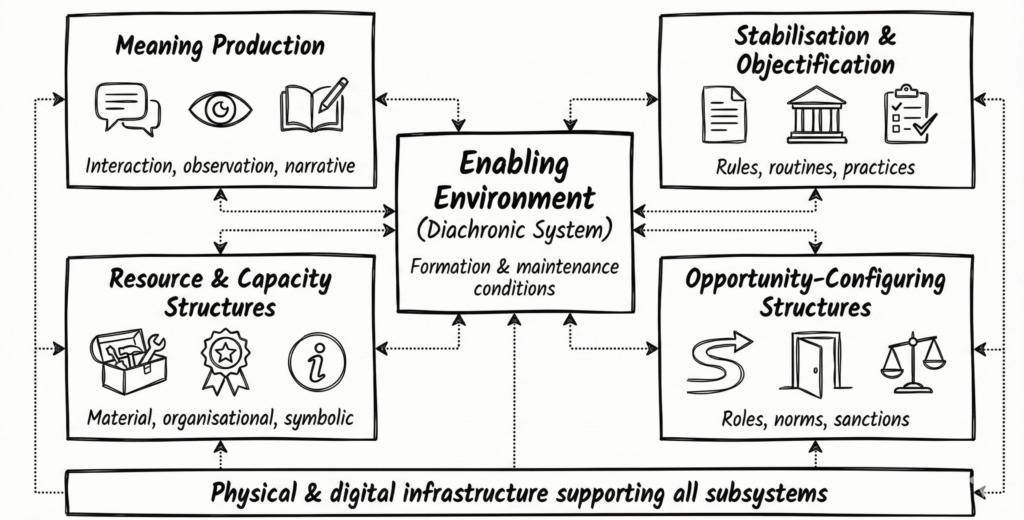

This includes governance arrangements, procedural consistency, institutional practices, access to resources, and the social and digital infrastructures that structure everyday interaction (refer to Figure 4). These elements are not the durable stock of social capital themselves, but they strongly influence how repeated experiences reinforce or erode relational capacity.

The enabling environment is especially important because its effects are often cumulative and delayed. An intervention may leave existing social capacity apparently intact while altering the conditions that support its future formation or maintenance. Over time, these changes shape what kinds of social capacity persist, weaken, or emerge, with significant implications for a range of substantive issues.

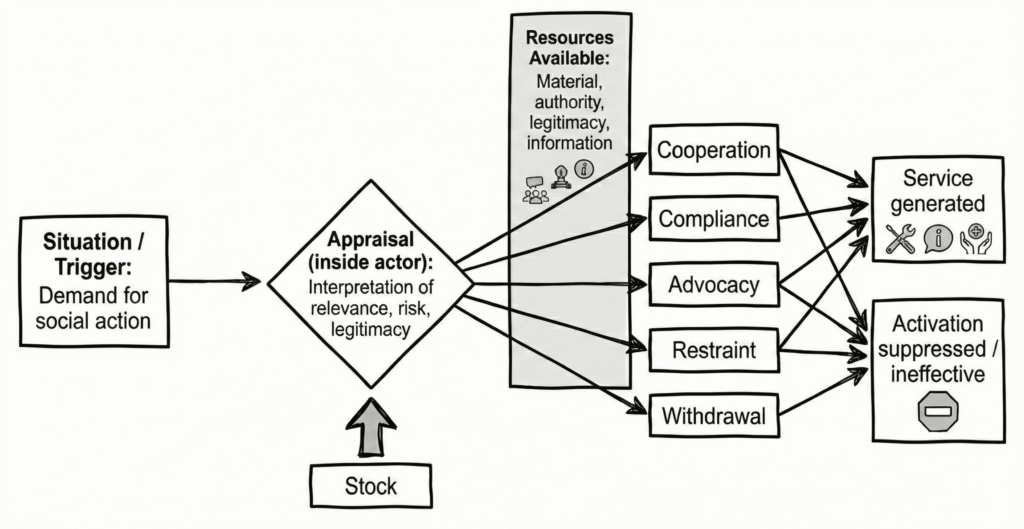

4.3 Activation contexts: when capacity is called upon

The third component of the system concerns activation: the situations in which social capacity is called upon in practice (refer to Figure 5). Activation occurs when actors encounter circumstances that require social action and assess, often implicitly, whether their relational capacity is relevant, safe, and likely to be effective.

Activation contexts are shaped by cues of legitimacy, risk, opportunity, and expected efficacy. They are also shaped by access to resources at the point of action, including authority, information, organisational backing, and time. Social capacity may exist but remain unexpressed when these conditions are hostile or constraining.

For impact assessment, this distinction is critical. SCIA treats non-activation as something to be explained, not assumed. Silence, withdrawal, or resistance may reflect constrained activation rather than degraded capacity. Distinguishing between these possibilities allows more accurate diagnosis and avoids repeatedly applying remedies that address the wrong part of the system.

4.4 System interaction and service-generation capacity

These three components, capacity, conditions, and activation, interact continuously. Experiences of activation feed back into social capacity, reinforcing or reshaping future orientations. Changes in the enabling environment alter how future situations are interpreted. Over time, these interactions determine the service-generation capacity of the system: how reliably, scalably, and robustly social capacity can be converted into collective benefits under varying conditions.

SCIA focuses on this system-level capacity rather than on isolated outcomes. Doing so explains why similar interventions can produce divergent long-term trajectories, why short-term success can coexist with growing fragility, and why efforts to improve social outcomes often fail when underlying conditions remain misaligned.

Understanding social capital as a system is, therefore, what allows it to function as an impact assessment lens rather than a descriptive label. It provides the structure needed to assess how decisions shape future social capacity, and to steward the conditions on which collective action depends.

5. The core questions the social capital lens enables

Using social capital as an impact assessment lens changes the nature of the questions that can be asked about decisions and their consequences. Rather than focusing only on immediate social responses or short-term outcomes, it enables decision-makers to examine how choices shape the future capacity for collective action. The broad questions set out below are designed to make that capacity visible in ways that are directly relevant to planning, design, approval, and governance.

| SCIA Question | What This Allows Decision-Makers to See |

| How does this decision affect future social capacity? | Whether relational conditions for cooperation and legitimacy are being strengthened or weakened |

| How does this decision shape the conditions that sustain social capacity? | Whether governance, infrastructure, and institutional practices support or erode capacity over time |

| How does this decision alter the situations in which social capacity is expressed? | Whether social capacity can be safely and effectively mobilised when needed |

| What does this mean for the system’s ability to generate value over time? | Whether social outcomes will remain reliable, scalable, and resilient under uncertainty |

Table 1. Core SCIA Questions: SCIA shifts the focus from immediate social response to future feasibility.

These questions are not theoretical abstractions. Each corresponds to a distinct aspect of the social capital system described in the previous section and addresses an important category of issues relevant to impact assessments. Asked together, they allow decision-makers to distinguish between surface effects and underlying capacity, and to identify where social risk or opportunity is emerging before it becomes entrenched.

This section outlines the questions; later sections describe the SCIA process and the methods used to address them.

5.1 How does this decision affect future social capacity?

The first question focuses on impacts on social capital as a durable form of capacity. It asks whether a decision is likely to strengthen, weaken, or reconfigure the relational conditions that shape how people orient toward others and institutions over time.

This includes effects on expectations of legitimacy, fairness, reliability, and mutual recognition, factors that influence whether cooperation, compliance, or collective effort are perceived as plausible and worthwhile in future situations. Importantly, changes at this level may not produce immediate behavioural effects. Social capacity can be strengthened or degraded well before it is expressed in visible action. Using the social capital lens allows assessment to recognise these shifts without waiting for conflict, disengagement, or institutional failure to emerge.

This question is especially important where decisions rely on existing goodwill or cooperation to succeed in the short term. It helps identify when that capacity is being reinforced, and when it is being quietly drawn down.

5.2 How does this decision shape the conditions that sustain social capacity over time?

The second question focuses on the enabling environment. It asks how a decision affects the institutional, infrastructural, and experiential conditions through which social capacity is formed, stabilised, and renewed over time.

This includes changes to governance arrangements, procedural consistency, access to resources, communication practices, and the quality of social and digital infrastructure. These conditions shape repeated experience and therefore influence how relational capacity evolves, often in cumulative and delayed ways. An intervention may leave existing social capacity apparently intact while altering the conditions that support its future formation.

Using the social capital lens brings these effects into view. It allows assessment to recognise when future capacity is being supported or eroded through changes to everyday conditions, even when short-term social outcomes appear favourable. This is critical for avoiding situations in which apparent success masks growing fragility.

5.3 How does this decision alter the situations in which social capacity is expressed?

The third question concerns activation. It asks whether and how a decision changes the contexts in which social capacity is likely to be mobilised in practice.

This involves examining the situations where social action will be required and considering how cues of legitimacy, risk, opportunity, and expected efficacy are likely to be interpreted. It also involves assessing whether actors have access to the resources they need at the point of action, such as authority, information, organisational backing, and time. Social capacity may exist but remain unexpressed if these conditions make action unsafe, ineffective, or costly.

Using the social capital lens makes it possible to distinguish between lack of capacity and constrained activation. Silence, withdrawal, or resistance are not automatically interpreted as evidence of weak social capital. Instead, they are treated as signals that activation conditions may be misaligned. This distinction improves diagnostic accuracy and helps ensure that responses target the appropriate part of the system.

5.4 How do these changes affect the system’s ability to generate value over time?

The fourth question integrates the previous three. It asks how changes to social capacity, enabling conditions, and activation contexts interact to affect the system’s overall service-generation capacity.

Rather than defining social capital by outcomes, this question focuses on whether the system is becoming more or less capable of supporting collective action across a range of situations and under varying conditions, including uncertainty and stress. It considers the reliability with which capacity can be converted into action, the scalability of that action across contexts, and the robustness of the system when circumstances change.

Box 2. Diagnosis with the social capital lens

Observed problem:

Low participation and growing disengagement in a community programme.

Common diagnosis:

“Lack of trust” or “community apathy.”

Typical response:

Increase engagement activity, add communications, and run more consultations.

What the social capital lens reveals:

Underlying social capacity remains strong, but activation contexts are constrained. Participants face reputational risk, unclear authority, and limited ability to influence outcomes. Social capital exists but cannot be safely or meaningfully expressed.

Implication for action:

The issue is not deficient social capital, but misaligned activation conditions. Adjusting governance arrangements and decision authority is likely to restore participation more effectively than additional engagement.

This integrated perspective allows trade-offs to be examined explicitly. For example, a decision may improve short-term efficiency by suppressing contestation while weakening long-term legitimacy, or it may slow delivery while strengthening future adaptability. The social capital lens does not resolve these trade-offs automatically, but it makes them visible and discussable.

5.5 Why these questions matter together

Each of these questions addresses a different dimension of long-term impact. Considered in isolation, they can be misleading. Focusing only on capacity overlooks structural erosion. Focusing only on conditions overlooks meaning. Focusing only on activation overlooks latent potential. The value of the social capital lens lies in addressing all four questions together and examining how they interact over time (see Box 2).

For decision-makers, this integrated approach provides a practical advantage. It allows social considerations to be incorporated into planning and governance in the same forward-looking way as other forms of impact, making future social capacity visible, comparable, and manageable before it becomes a constraint. In doing so, it turns social capital from an implicit dependency into an explicit object of assessment and stewardship.

The next section explains how these questions are addressed in practice through a structured SCIA process that aligns assessment stages with the causal properties of the social capital system.

6. Applying the social capital lens in practice: the SCIA process

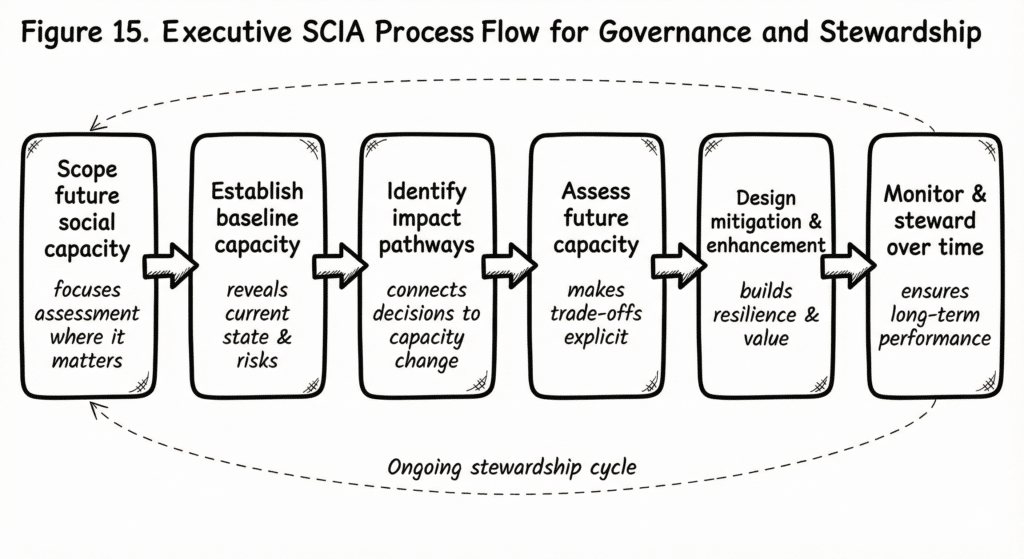

If social capital is to function as an impact assessment lens, it must be applied through a process that fits how decisions are actually made. SCIA provides such a process. Its purpose is not merely prediction or optimisation, but structured judgement about how decisions shape future social capacity.

For social capital to inform real choices, it must be translated into an assessment process that supports judgment under uncertainty, and can be integrated into existing planning, approval, and governance arrangements. SCIA focuses on identifying plausible pathways of influence, examining how design and governance choices condition future possibilities, and supporting informed deliberation about risk, robustness, and trade-offs.

The SCIA process translates the questions enabled by the social capital lens into a sequence of assessment stages that are familiar to practitioners working in impact assessment, risk management, and strategic planning (refer to Figure 6).

These stages are not intended as a rigid checklist, but as an organising structure that helps ensure attention is given to the key dimensions of future social capacity. Each stage focuses on a different aspect of how social capital is shaped, sustained, or constrained, reducing the risk that social considerations remain implicit or are addressed only after problems emerge.

Taken together, the process provides a bridge between conceptual insight and practical application. It allows the social capital lens to be applied proportionately across different decision contexts, from early design and policy development to approval conditions and implementation oversight.

The sections that follow describe each stage of the SCIA process in turn, showing how the lens can be used systematically to support clearer judgment, earlier identification of social risk and opportunity, and more deliberate stewardship of the social conditions on which long-term outcomes depend.

6.1 SCIA as a governance capability

Taken together, these stages position SCIA as a governance capability rather than a one-off study. The SCIA process mirrors how other forms of impact assessment contribute to long-term decision quality by informing design, approval, implementation, and oversight, while remaining tailored to the distinctive properties of social capital as a source of future capacity that is shaped cumulatively and expressed contextually.

Viewed in this way, SCIA supports governance by improving how organisations anticipate and manage the social conditions on which their decisions depend. It provides a structured means of considering how policies, projects, and institutional arrangements influence future cooperation, legitimacy, and adaptability, and of revisiting those judgements as conditions evolve. This allows social considerations to be incorporated into governance processes not as ad hoc concerns, but as part of an ongoing cycle of foresight, review, and adjustment.

By applying the social capital lens through a structured process, SCIA enables organisations to move from implicit reliance on social capital to more explicit stewardship of the conditions that make collective action possible. It makes visible when social capacity is being reinforced, when it is being drawn upon without replenishment, and when changes to governance or design may be increasing future fragility. In doing so, SCIA supports clearer accountability for the long-term social implications of decisions.

7. Methods aligned to the social capital system

SCIA is not defined by a fixed toolkit. It is defined by the alignment between what is being assessed and how it is assessed. Because social capital operates as a system comprising distinct components, stock, enabling environment, activation context, and service-generation capacity, no single method can adequately capture it. SCIA therefore uses a deliberately plural, mixed-method approach in which different forms of evidence are brought to bear on different parts of the system.

This alignment is essential. Many weaknesses in existing social assessments arise not from lack of data, but from asking methods to do analytical work they are not suited to, such as inferring future capacity from present behaviour, or treating infrastructure or institutions as proxies for social capital itself. SCIA avoids these errors by matching methods to the causal properties of each system component.

Table 2 summarises how this alignment is operationalised in practice, and the following sections describe them in more detail. It maps each component of the social capital system to the analytical purpose it serves and the families of methods most suited to that task. The table illustrates how SCIA differentiates methodological roles across the system and integrates evidence to support judgment about future social capacity.

| SCIA focus | Analytical purpose | Primary method types |

| Social capital stock | Understand durable relational orientations that condition future action | Structured interviews; narrative elicitation; deliberative workshops; orientation-focused surveys; document and media analysis |

| Enabling environment | Assess conditions that shape formation and maintenance of social capital over time | Governance and institutional analysis; policy and procedural review; social and digital infrastructure assessment; walk-throughs; user-experience methods; service journey mapping |

| Activation contexts | Examine how and when social capital is mobilised or suppressed in practice | Scenario analysis; process tracing; resource and authority mapping; organisational analysis; constraint and opportunity analysis |

| Service-generation capacity | Judge system-level ability to convert social capital into reliable, scalable outcomes | Synthesis; comparative analysis across cases or scenarios; structured expert judgement; pathway comparison |

Table 2. Summary of analytical purpose and possible methods

7.1 Assessing the stock of social capital

Because social capital as a stock operates at the level of meaning, expectation, and relational orientation, it cannot be assessed reliably through behavioural observation alone. The most appropriate methods are those capable of surfacing durable interpretive predispositions, rather than momentary opinions or reactions.

SCIA therefore draws on interpretive and qualitative approaches such as structured interviews, narrative elicitation, deliberative workshops, and carefully designed surveys that focus on generalised orientations rather than attitudes toward specific decisions. Questions are framed to explore how actors interpret legitimacy, fairness, reliability, and recognition over time, and how these interpretations extend beyond particular others and particular encounters to include generalisable orientations towards certain others, groups, and organisations.

Importantly, SCIA also treats indirect and mediated experience as analytically relevant. Public communication, institutional signalling, policy narratives, and observed treatment of others can all shape relational predispositions, even among actors who are not directly engaged. Document analysis, media analysis, and review of institutional messaging are, therefore, legitimate sources of evidence when assessing stock-level impacts.

The purpose at this stage is not to measure trust or sentiment in isolation, but to understand how relational meaning is being formed and stabilised in ways that will condition future action.

7.2 Assessing the enabling environment

The enabling environment is assessed using methods that focus on durable conditions rather than states. Because it operates diachronically, shaping formation and maintenance over time, appropriate methods examine structures, practices, and experiential conditions that persist across situations.

This includes analysis of governance arrangements, rules and procedures, enforcement practices, and institutional consistency. It also includes assessment of social and digital infrastructure: whether interaction opportunities are accessible, legible, inclusive, and capable of supporting repeated engagement over time. The presence of infrastructure is not sufficient; SCIA examines its nature, governance, and demand properties that determine how it is experienced and used in practice.

Experiential and demand-side methods are particularly important here. Walk-throughs, user-experience techniques, service journey mapping, and participatory design reviews can reveal how environments shape perceptions of safety, dignity, recognition, and efficacy. These factors play a central role in whether relational predispositions are reinforced or eroded, yet are often invisible in conventional assessments.

At this level, SCIA deliberately avoids inferring changes in social capital stock. The enabling environment is assessed for its capacity to support formation and maintenance, even where existing social capital remains temporarily intact.

7.3 Assessing activation contexts

Activation contexts are assessed using situational and pathway-based methods that focus on how social capital is mobilised, or suppressed, in practice.

Scenario analysis is central. SCIA identifies plausible situations in which social action will be required, such as implementation phases, moments of conflict, transitions, crises, or opportunities for collective benefit. For each scenario, the assessment examines how actors are likely to appraise the situation, what carriers of expression are available, and what risks or constraints accompany action.

Resource and authority mapping is also critical. Administrative data, organisational analysis, and process mapping are used to identify what material, informational, organisational, or symbolic resources are available at the point of activation, and who has access to them. SCIA treats misalignment between social capital and available resources as analytically significant because it can suppress expression even when relational predispositions are strong.

Attention is also given to opportunity and constraint structures: visibility, surveillance, power asymmetries, role expectations, and sanction regimes that shape whether expression is perceived as safe or worthwhile. Non-activation is treated as something to be explained, not as evidence of social deficit.

7.4 Assessing system service-generation capacity

The final analytical task is to assess how changes to social capital stock, enabling environments, and activation contexts interact to affect the service-generation capacity of the social capital system as a whole. This capacity refers to the system’s ability to convert social capital into effective collective action across a range of situations and over time. It cannot be measured directly, nor reduced to a single indicator, because it reflects interaction effects rather than isolated attributes.

SCIA therefore relies on synthesis, comparative reasoning, and structured judgement. Evidence generated in earlier stages is integrated to assess whether the system is becoming more or less capable of converting social capital into reliable, scalable, and robust services across domains and under varying conditions. The focus is on overall system performance, including its resilience under stress, adaptability to change, and sensitivity to shifts in context.

Comparisons across scenarios, time periods, or similar systems are particularly valuable because they help identify recurring vulnerabilities, reinforcing dynamics, and leverage points. Where scoring or rating frameworks are used, they are treated as aids to judgement rather than definitive measures, and are explicitly grounded in the underlying evidence and assumptions developed through earlier analysis.

7.5 Why methodological alignment matters

The strength of SCIA lies not in methodological novelty, but in methodological fit. Interpretive methods are used where meaning matters. Structural methods are used where durability matters. Situational methods are used where activation matters. Synthesis is used where system performance matters.

By aligning methods to the causal architecture of the social capital system, SCIA avoids common inferential errors: equating behaviour with capacity, treating institutions as capital, or defining social capital by outcomes. This alignment allows SCIA to remain flexible across contexts while retaining analytical discipline.

The next section turns from method to value, explaining what SCIA enables in practice and why this form of assessment reveals risks and opportunities that other approaches systematically miss.

8. What SCIA enables in practice

The value of SCIA lies not in adding another analytical layer, but in changing what organisations are able to see, anticipate, and govern. By treating social capital as a system of future capacity rather than as a collection of outcomes or sentiments, SCIA enables forms of insight and decision support that are difficult or impossible to achieve through existing approaches alone.

Box 3. Small activity changes, large effects

A project team regularly meets with local stakeholders to discuss implementation issues. Rather than changing the scope of engagement, the team makes a simple adjustment to the meeting format: part of each meeting is devoted to a shared task, such as jointly prioritising issues or sequencing next steps, rather than open discussion alone.

This change requires no additional resources, but it alters how participants relate to one another. Repeated task-based interaction increases familiarity, mutual recognition, and expectations of cooperation. Over time, coordination improves, informal problem-solving increases, and resistance during later stages declines.

From a SCIA perspective, the benefit arises not from additional participation, but from a small change in activity structure that strengthens social capital through repeated experience, with effects that accumulate well beyond the immediate interaction.

One of the most immediate benefits of SCIA is earlier visibility of social risk and opportunity. Many of the risks that undermine projects, policies, and institutions, loss of legitimacy, coordination failure, resistance, disengagement, and fragility under stress, emerge slowly and indirectly. They rarely appear as “social issues” at the point where decisions are made.

SCIA brings these dynamics forward by showing how interventions affect the conditions that make future cooperation and collective action possible. This allows organisations to anticipate social risk upstream, when design choices and governance arrangements can still be adjusted at relatively low cost.

Crucially, this upstream visibility often reveals that relatively small changes can have disproportionate effects on future social capacity (refer to Box 3). Modest adjustments to activities, decision processes, physical or digital environments, or the interpretive cues through which actions are understood can significantly alter how social capital is formed, sustained, or expressed.

Because social capital accumulates through repeated experience, such changes may involve little additional expenditure yet generate substantial returns over time by strengthening cooperation, reducing friction, and increasing the reliability with which collective action can be mobilised.

SCIA also improves diagnostic accuracy. In many settings, weak participation or visible resistance is interpreted as a lack of trust or social capital. SCIA enables a more precise diagnosis by distinguishing between thin or degraded social capital and situations where social capital exists but cannot be activated because contexts are hostile, risky, or resource-poor.

This distinction matters because it determines the appropriate response. Efforts to “build trust” will fail if the problem lies in governance design or activation conditions, just as institutional reform will fail if underlying relational predispositions have been eroded. SCIA helps organisations avoid repeatedly applying the wrong remedies.

Another practical contribution of SCIA is that it makes trade-offs explicit. Many interventions generate short-term gains by drawing on existing social capital without replenishing it, or by suppressing contestation in ways that weaken long-term legitimacy. Other interventions may appear slower or more costly initially, but strengthen the system’s capacity to adapt, learn, and scale over time.

SCIA does not resolve these trade-offs automatically, but it makes them visible and discussable. This allows decision-makers to weigh immediate benefits against future capacity deliberately, rather than discovering the consequences retrospectively.

SCIA also provides a defensible basis for investment in social conditions that are otherwise difficult to justify. Expenditure on procedural integrity, institutional consistency, social infrastructure, or relational work is often vulnerable to being seen as discretionary or “soft.”

By situating these investments within a capital framework, SCIA shows how they contribute to the maintenance and activation of a form of capital that underpins long-term value across domains. This shifts the rationale from goodwill to stewardship, and from preference to responsibility.

Importantly, SCIA also reveals that not all effective interventions require large or dedicated investments. In many cases, the most consequential impacts on social capital arise from how existing activities are designed, sequenced, or signalled: who is involved when, how decisions are explained, how authority is exercised, and how lived experience aligns with formal intent.

SCIA helps identify these leverage points, enabling organisations to enhance social capacity through careful attention to conditions rather than through costly standalone initiatives.

A further benefit is that SCIA supports design quality and adaptability. By tracing how impacts propagate through the social capital system, SCIA highlights leverage points that are often overlooked: sequencing of decisions, clarity of authority, visibility of commitment, alignment between formal rules and lived experience, and availability of resources at moments of activation. Attention to these factors improves not only social outcomes but also overall system performance, particularly in complex or uncertain environments.

SCIA also strengthens institutional learning. Because it focuses on system properties rather than isolated outcomes, it allows organisations to compare experiences across cases, identify recurring patterns of social capital degradation or strengthening, and refine their approaches over time. This cumulative learning is difficult to achieve when social analysis remains tied to context-specific outcomes or engagement metrics.

Importantly, SCIA enables responsibility without overreach. It does not claim that organisations can engineer trust, guarantee cooperation, or control social behaviour. Instead, it clarifies the conditions for which organisations can reasonably be held responsible: the governance arrangements, institutional practices, and activation contexts they create. This supports accountability for stewardship without implying behavioural determinism or unrealistic expectations.

Taken together, these practical benefits reposition social capital from an implicit dependency to an explicit asset. SCIA allows organisations to recognise when they are relying on social capital, when they are drawing it down, and when they are strengthening the foundations of future action. In doing so, it supports a more mature form of governance, one that treats social capital with the same care, foresight, and deliberation as other forms of capital on which long-term performance depends.

The next section situates SCIA within the broader landscape of assessment and decision frameworks, clarifying how it complements existing approaches and how it can be integrated into established governance processes.

9. How SCIA complements existing frameworks

SCIA is not intended to replace established assessment or governance frameworks. Its value lies in addressing a distinct but complementary dimension of impact that is often relied upon implicitly rather than examined explicitly: the condition of future social capacity.

Social Impact Assessment (SIA) focuses on impacts on people and communities. It examines changes in wellbeing, livelihoods, access, equity, social relations, and lived experience arising from interventions, and plays a critical role in identifying who is affected, how impacts are distributed, and whether impacts are acceptable or require mitigation or management.

SCIA does not duplicate this work. Instead, it addresses a complementary analytical concern: how decisions shape the social conditions that influence whether such impacts endure, scale, or remain feasible over time.

Stakeholder engagement serves a different but related function within decision-making and implementation. It supports information exchange, participation, and procedural legitimacy, and often provides essential inputs into assessment processes.

While engagement activities can inform an SCIA, they are not themselves assessments of future social capacity. SCIA provides a way of examining how engagement practices, and the broader intervention of which they form part, affect the longer-term conditions for cooperation, legitimacy, and collective action beyond the immediate decision.

SCIA also complements economic appraisal and risk management. Economic and financial analyses typically rely on assumptions about cooperation, compliance, institutional reliability, and behavioural response, even when these assumptions are not made explicit. SCIA brings these dependencies into view by examining the social conditions on which they rest.

Similarly, many strategic and operational risks are socially mediated; SCIA offers a structured means of identifying where future social capacity may be strengthened, constrained, or become fragile under stress.

Across these frameworks, SCIA functions as an integrative lens rather than a parallel process. It extends established impact assessment practice by making social capital—the capacity that enables collective action across domains—more explicit and assessable within existing governance and decision processes.

In doing so, it supports clearer judgment about long-term feasibility, risk, and robustness without displacing the roles of established assessment or engagement approaches.

Table 3 summarises how SCIA relates to and complements other commonly used frameworks, highlighting differences in analytical focus rather than relative importance or quality.

| Dimension | Social Capital Impact Assessment (SCIA) | Social Impact Assessment (SIA) | Stakeholder Engagement |

| Primary purpose | Assess how decisions shape future social capacity and the conditions for collective action over time | Assess impacts of interventions on people and communities | Inform, consult, and involve stakeholders in decision-making |

| Object of focus | Social capital system: durable social capacity, enabling conditions, and activation contexts | Social outcomes and lived experience (wellbeing, livelihoods, access, equity, social relations) | Interaction processes and stakeholder input |

| Core question | How do decisions affect the conditions that enable or constrain future cooperation and legitimacy? | Who is affected, how, and are those impacts acceptable or manageable? | Are stakeholders appropriately informed, heard, and involved? |

| Time orientation | Medium- to long-term; prospective and cumulative | Short- to medium-term, with some longer-term effects | Immediate and ongoing during planning and implementation |

| Unit of analysis | System-level social capacity and its durability | Individuals, groups, and communities | Stakeholders and participation processes |

| Treatment of social capital | Treated explicitly as a form of capital with causal significance | Often implicit or embedded within social outcomes | Often assumed or treated as a by-product of engagement |

| Typical methods | System scoping, pathway analysis, institutional and governance analysis, scenario reasoning, synthesis | Surveys, interviews, participatory appraisal, impact prediction, mitigation planning | Meetings, workshops, consultations, communications, feedback |

| What it explains well | Long-term performance, resilience, legitimacy, coordination, and system fragility | Distribution and significance of social impacts | Procedural quality and stakeholder perspectives |

| What it does not attempt | Measure satisfaction or predict specific social behaviours | Assess future social capacity or capital dynamics | Diagnose system-level social capacity or risk |

| Role in decision-making | Strategic and governance-oriented; informs design, sequencing, and stewardship | Impact management and accountability | Process support and decision legitimacy |

| Relationship to others | Complements SIA and engagement by focusing on future social capacity | Complements SCIA by explaining experienced impacts | Provides inputs that may inform SIA or SCIA |

Table 3. Comparison of SCIA, Social Impact Assessment, and Stakeholder Engagement

The following section draws these threads together, returning to the central proposition of the paper: that because long-term performance depends on social capital, responsible governance requires not only recognising its importance, but deliberately assessing and stewarding the conditions under which future social capacity is formed, sustained, and activated.

10. From social outcomes to stewardship of social capacity

This paper has advanced a practical proposition: many of the outcomes that impact assessment seeks to safeguard, including effective delivery, legitimacy, resilience, adaptability, and long-term value, depend on social conditions that shape whether people and institutions are able and willing to act together over time. These conditions are already relied upon in decision-making, but they are not always examined explicitly as part of assessment.

Treating social capital as a form of future capacity provides a way to make these conditions visible without redefining what matters. Rather than focusing solely on experienced social outcomes, the social capital lens draws attention to how decisions shape the underlying capacity that enables such outcomes to persist, scale, or adapt.

This shift does not displace existing social analysis; it extends it by introducing a prospective perspective on durability, cumulative effects, and system robustness.

SCIA has been presented as a structured way to apply this perspective within established impact assessment and governance processes. By distinguishing analytically between social capital as a stock of durable capacity, the environments that shape its formation and maintenance, and the contexts in which it is activated, SCIA enables more precise judgment about how interventions influence future social capacity.

This structure allows decision-makers to identify when social capital is being reinforced, when it is being drawn upon without replenishment, and when changes to system conditions may quietly increase future fragility.

Importantly, SCIA supports stewardship rather than control. It does not assume that social responses can be specified in advance or that collective behaviour can be engineered. Instead, it clarifies the aspects of the social system for which organisations and institutions can reasonably be held responsible: the design of activities, governance arrangements, institutional practices, and enabling environments that shape how social capacity develops and is expressed over time. In doing so, it aligns social considerations with how other forms of capital are treated in long-term decision-making.

As pressures on institutions and communities intensify, from economic volatility and environmental change to social fragmentation and declining trust, the costs of mismanaging social capital are becoming more visible.

At the same time, the benefits of interventions that strengthen the social capital system often extend far beyond their original scope, supporting adaptability, resilience, and long-term value in ways that are rarely captured by conventional metrics. SCIA provides a way to learn from both, systematically and prospectively.

By making social capital explicit as an object of assessment, SCIA also supports more deliberate and proportionate action. Many of the most consequential influences on social capacity arise not from large programmes or dedicated interventions, but from small, repeated design and governance choices whose effects accumulate over time.

SCIA helps identify these leverage points early, allowing adjustments to be made when they are least costly and most effective.

In this sense, SCIA represents a shift from implicit reliance on social capital to explicit stewardship of the conditions that sustain it. It enables impact assessment to engage more fully with the social dimensions of long-term performance, without expanding scope unnecessarily or undermining existing practice.

Where decisions depend on people acting together over time, as they invariably do, treating social capital as future capacity provides a clearer basis for anticipation, responsibility, and learning.

11. References

Fisher, I. (1906). The nature of capital and income. Macmillan.

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510.

Hicks, J. R. (1946). Value and capital (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Jorgenson, D. W. (1963). Capital theory and investment behavior. American Economic Review, 53(2), 247–259.

Ostrom, E. (2000). Social capital: A fad or a fundamental concept? In P. Dasgupta & I. Serageldin (Eds.), Social capital: A multifaceted perspective (pp. 172–214). World Bank.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster.

Robinson, L. J., Schmid, A. A., & Siles, M. E. (2002). Is social capital really capital? Review of Social Economy, 60(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346760110127074

Woolcock, M. (2001). The place of social capital in understanding social and economic outcomes. Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2(1), 11–17.

World Bank. (1998). The initiative on defining, monitoring and measuring social capital: Overview and program description. World Bank Social Development Department.

12. Further information

Social Capital Impact Assessment (SCIA) is an emerging governance and assessment capability concerned with understanding how decisions shape the social capital systems that underpin long-term performance, legitimacy, resilience, and wellbeing.

Readers interested in applied examples, methodological notes, or further discussion of SCIA in specific decision contexts (such as infrastructure planning, policy design, organisational change, or community investment) are invited to engage with the author and the Institute for Social Capital.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks colleagues and collaborators who provided feedback on earlier drafts of this paper and contributed to the development of Social Capital Impact Assessment through discussion and applied work. Any errors or omissions remain the responsibility of the author.

About the author

Tristan Claridge is the Director of the Institute for Social Capital and President of the International Social Capital Association. Tristan Claridge has over 20 years of experience researching and applying social capital to a wide range of contexts. He is a geographer and environmental scientist with a passion for sustainable development and poverty alleviation. He takes an interdisciplinary perspective by combining the lessons of economics, sociology, political science, psychology, urban planning, and any other discipline that contributes to understanding the concept. Tristan has a Masters degree from the University of Queensland, Australia, which included environmental impact assessment, social impact assessment, social planning for development, urban planning, and natural resource management. Read more at www.tristanclaridge.com

About the Institute for Social Capital

The Institute for Social Capital is an independent research and practice organisation dedicated to advancing understanding of social capital and its role in social, economic, and institutional outcomes. The Institute works across research, policy, and applied settings to support more effective stewardship of social capital.